I am currently lead developer for a French press website with very high traffic. Along my previous work experiences, I was able to perform development on several other high volumetry sites as well.

When with only a dozen or so servers you need to contain traffic peaks between 100,000 and 300,000 short term visitors, the cache ceases to be optional: it becomes an absolute necessity !

Your application may have the best performance possible, you will always be limited by your physical machines - even if this is no longer true in the cloud (with an unlimited budget) – Consequently you must make friends with the cache.

Based on the experience that I have been able to accumulate on the subject and the numerous traps into which I have fallen, I will try to give you the best solutions for the use of the different caches.

You must have often heard, or said yourself, "empty your cache", when testing the functionalities of your website. You even probably know the following keys by heart:

source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cache_web

Don't worry, there is a solution; the purpose of this article is to enable you to finally get to grips with the HTTP cache.

Principle of the HTTP Cache

The HTTP cache uses the same principle as all caches; it is simply a key/value recording.

How is the key chosen? And what is the value?

The key is a unique value which enables you to recognize a web page; you are probably beginning to understand that it is obviously the URL. As for the stored value, it is the content of your page in all possible formats (text, html, json, etc.).

The HTTP cache makes possible a lot of things that we shall see as the article progresses.

But how can I use all these features?

You simply need to look at what an HTTP query contains. In its simple version, a query contains a header and some content. The content is what the browser displays; more often than not this is your HTML page. As for the header, it contains all the essential data of the page, the best known being the "status code" allowing us to know the status of the page (200 OK, 404 Not Found, 500 error); but it is also the place where your HTTP cache is configured. Many of the headers can be changed to improve and configure your cache.

Configuring your HTTP cache

Now that we know where we need to configure our cache,

what can we configure?

First of all, let us enable the cache for our page. To do this we must add the header.

Cache-Control: public

There are other settings for this header that I suggest you find here: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cache-Control. One of the most used is:

Cache-Control: no-store

serving to disable the cache on the page.

We can now configure the cache time of the page; this is what is called the TTL of the page. For this, the header to be changed is the following:

max-age: 300

300 being a cache time in seconds.

In some of the documentation available you can find a very similar header:

s-max-age: 300

It has the same function as the max-age header but it can be used on a proxy (e.g.: Varnish) and therefore with a different TTL for the CDN and the proxy.

You can also choose an expiry date which makes it possible to be even more specific with the cache; the header is simple:

Expires: Thu, 25 Feb 2016 12:00:00 GMT

With these three headers, you can already use the cache with a good level of precision; by managing your TTL and timeouts you can make your pages live and let them uncache themselves.

But how can I uncache them at will?

The HTTP cache has a very useful feature to request the server to calculate if it needs to deliver a new page. To use it, simply fill in a new header when generating the page.

Last-Modified: Wed, 25 Feb 2015 12:00:00 GMT

The client (your browser) sends a header in its request to the server.

If the server delivers a date that is more recent than that of the client, the client takes the new page. Otherwise, it keeps the page in the cache.

This also allows you to manage response 304 which allows the server to send only the header of the response (i.e. an empty content); this reduces the bandwidth used by the server. For this, the server must have the intelligence to read the Last-modified header and if the new date generated is not more recent, it may deliver an HTTP request 304 allowing the client to keep its cache.

There is another header with the same principle; it is the Etag header, which is configured with a 'string' generated by the server which changes according to the content of the page.

Etag: home560

Be careful, the calculation of the ETag must be very carefully considered because it governs the cache time of the page, so it must be calculated with the dynamic data of the page.

As explained in the first chapter, the key of the HTTP cache is the URL of the page. This can be a nuisance if your page is dynamic depending on the user, because the URL will be the same, but the content will be different. It will therefore be necessary to cache several contents for one URL. Fortunately, Tim Berners-Le, the inventor of the HTTP protocol provided for this event by adding the header:

Vary: Cookie User-agent

As its name indicates, it allows you to vary the cache by using another header, e.g.: 'User-agent' which allows you to store, for one URL, all the pages for each user-agent (e.g.: mobile page and desktop page). The cookie allows you to store one page per cookie (hence per user).

We have just made a rather comprehensive tour of the possible configurations for the HTTP cache, but it is also possible to add one's own headers. Before moving forward on this topic, we shall look at the architecture of the HTTP cache.

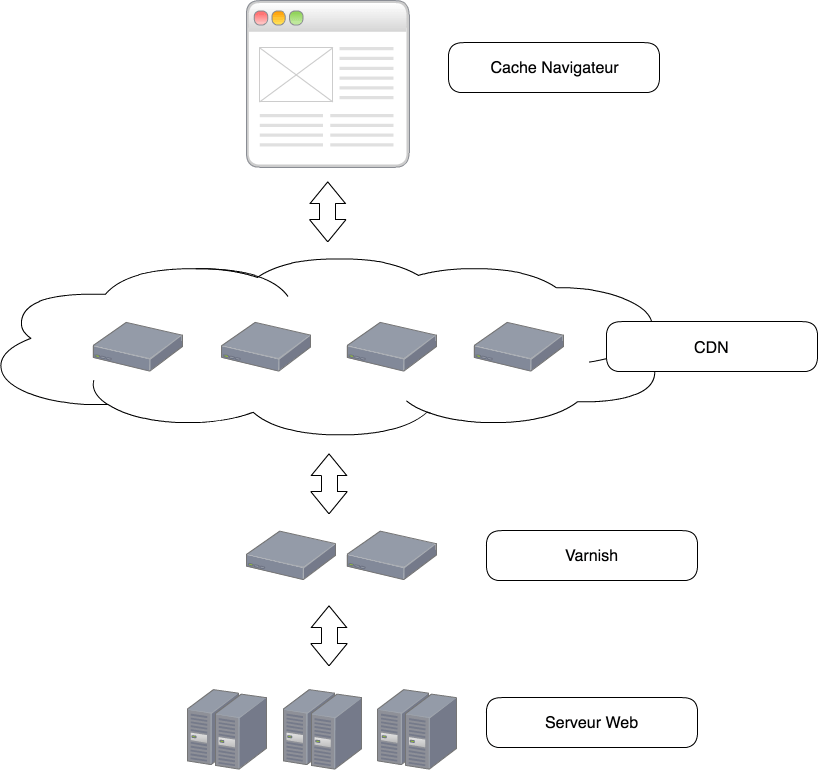

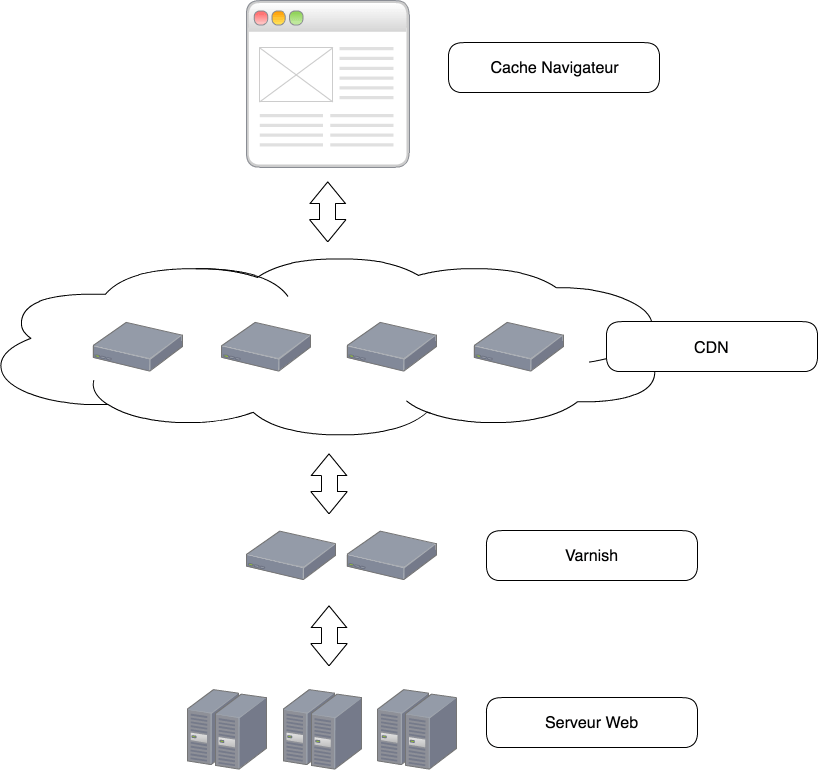

Classic HTTP cache architecture

You know how to configure your cache like a professional.

But where should you place your cache?

The HTTP cache can be used in several places in your architecture; each place has specificities and allows an improvement in performance.

The browser

This is the HTTP cache closest to your user; this allows it to be very fast. The only concern is that it is linked to the user; consequently it may be empty quite often, for example on the first connection. It may also be emptied by the user or even disabled. Consequently the resilience of this cache is not allocated to you; it must therefore be paired with another HTTP cache.

The CDN

The Content Delivery Network is a network of computers to serve content (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Content_delivery_network). It is external to the architecture and its specialty is geolocation, it therefore allows a user to go onto the nearest CDN. You have probably already used one when you use a JS tag, e.g.: jquery, angular, etc. …, and if you use the URL provided rather than the downloaded file.

The main advantage of the CDN is to have many servers across the world and allow you not to receive all the traffic to the site on your servers. If you have already worked for a high traffic site, the CDN is the best way not to maintain 10,000 servers for your application. The cost of a CDN is often linked to the bandwidth, hence it is important to cache only what you need and use the most possible 304s.

The cache proxy, Varnish

It acts like the CDN, and the CDN belongs to the architecture. It often concerns servers that you maintain, it requires a lot of RAM (the storage is done there). The Varnish or other cache technology allows finer configurations than a CDN and above all allows the use of one's own headers. It also allows use of the ESI that we shall see in the next chapter. (Akamai, the inventor of ESI is a CDN)

The Web Server

The web server also allows you to use the HTTP cache, it is generally used for the cache of assets (JS, CSS, images, etc.). Like Varnish, its advantage is to be very finely configurable.

Customizing your HTTP cache

The advantage of the HTTP cache is that it is very simple to use, and that most of the web frameworks put in place simple interfaces to use it. Despite a great number of features, we always need more; it is for this reason that for a project on a high traffic site we place two Varnish custom headers, which can help.

The catalog

X-Varnish-Catalog: |home|345|567|

This is a header that references your page, either by name (home, page, etc.), or by object ID.

But to do what?

To allow you to easily find all pages stored in Varnish and that reference a particular object; if you can find them, you can delete them, and hence generate a cache. To do this, it is necessary to configure Varnish to create a ban of a URL. Here is a little code easy to set up:

# Ban - Catalogue decache

#

# How to ban all objects referencing <my_tag> in the X-Cache-Varnish-Catalog header

# curl -X BAN http://<varnish_hostname>/uncache/<my_tag>

# Object header ex. : X-Cache-Varnish-Catalog: |1235|9756|546|687|37436543|<my_tag>|region-centre|

if (req.method == "BAN") {

if (!client.ip ~ invalidators) {

return (synth(405, "Ban not allowed"));

}

if (req.url ~ "^/uncache/") {

ban("obj.http.X-Cache-Varnish-Catalog ~ |" + regsub(req.url, "^/uncache/([-0-9a-zA-Z]+)$", "") + "|");

return (synth(200, "Banned with " + req.url));

}

eturn (synth(200, "Nothing to ban"));

}

The Grace

X-Varnish-Grace: 300

As for the max-age, you must give it a time in seconds. This small header allows you to gain even more performance. It tells your Varnish the acceptable time to deliver a cache even after expiry of the max-age.

For a better understanding, here is an example:

Let’s take the page / home which has the header:

Cache-control: public

max-age: 300

X-varnish-grace: 600

Let’s imagine that Varnish has the page in its cache, if a user arrives at the 299th second, Varnish delivers the cache directly.

But what happens on the 301st second?

If it was not for the Grace, Varnish would have to call the server directly to obtain the response to be returned to the user. But with the Grace, Varnish will deliver its cache and ask the server for a new content, which allows you to avoid latency time for the user.

And now, on the 601st second?

Easy; your page is expired and the request arrives directly on your server.

Here is the configuration for Varnish:

sub vcl_backend_response {

# Happens after we have read the response headers from the backend.

#

# Here you clean the response headers, removing silly Set-Cookie headers

# and other mistakes your backend does.

# Serve stale version only if object is cacheable

if (beresp.ttl > 0s) {

set beresp.grace = 1h;

}

# Objects with ttl expired but with keep time left may be used to issue conditional (If-Modified-Since / If-None-Match) requests to the backend to refresh them

#set beresp.keep = 10s;

# Custom headers to give backends more flexibility to manage varnish cache

if (beresp.http.X-Cache-Varnish-Maxage) {

set beresp.ttl = std.duration(beresp.http.X-Cache-Varnish-Maxage + "s", 3600s);

}

if (beresp.http.X-Cache-Varnish-Grace && beresp.ttl > 0s) {

set beresp.grace = std.duration(beresp.http.X-Cache-Varnish-Grace + "s", 3600s);

}

}

The ESIs

You are now an expert in the use of the HTTP cache, only one thing is left to be understood: ESIs.

Edge Side Include (ESI) allows you to use the full power of Varnish. As stated above, this technology was invented by Akamai, one of the most famous CDNs.

What is it used for?

The simplest problem is the following.

On every page you have a block of pages which is always the same, but you must change it often. The solution is to uncache all pages containing the block; this can very quickly become a problem because your servers will be in demand too often.

ESIs serve in this situation. An ESI is simply a page with its own cache that can be inserted into another via an HTML tag.

//home.html

<html>

<body>

<esi url='block.html'/>

Test

</body>

</html>

Varnish will recognize the use of an ESI and will therefore cache two objects, one for the full page with the cache data of the page and one for ESI with other cache data. You can then uncache the ESI only and Varnish will update a single object (only one request to the server); the user has all the pages updated just the same.

For further information, I suggest you look at a previous article, which explains an implementation for Symfony.

You can also find a presentation about HTTP caches and Symfony ici.

.